by S. O. Coutant

Updated May 17, 2024

For decades the big-city newspapers in our neighborhood were the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Mirror. My family subscribed to the Times. Had this not been the case, chances are slim we would have learned of an opportunity to embark upon an adventure that would involve our entire family and last for sixty-five years.

One day in 1954 a co-worker of my dad, Bob Adam, described five-acre parcels of desert land available for homesteading from the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Bob said that his dad, who worked in the Monotype department of the Times, was buying a parcel, as were several other Times-Mirror employees. The fee was $25 an acre, with the stipulation that improvements had to be made in the form of a 400-square-foot dwelling to be built on the property within a specific time frame. (Read the next paragraph for an update.)

§ § §

2/2/2022 UPDATE—Today it was brought to my attention that on March 12, 1957, an announcement revealed that outright ownership of our five-acre parcels had become available. Covenants needed to be signed by property owners, but no longer was the BLM requiring improvements be made for ownership to be granted. The announcement of this 1957 event is here for reading and downloading.

§ § §

Along with our next-door neighbors in Sierra Madre, Clara and Marshall Annis, we drove to the BLM office one Saturday morning, and obtained information about which parcels were available for homesteading.

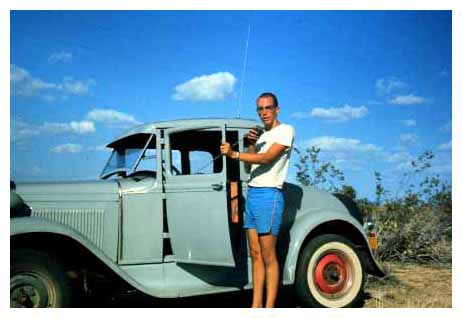

The following weekend we piled into our 1948 Studebaker Commander and headed over the Cajon Pass on our way to the desert, the first of what would become hundreds of repetitions of this journey. Interstate 15 did not yet exist. We used the narrow two-lane State Highway 66-91-395.

The 1948 Studebaker Commander at our camp

site a quarter-mile west of our parcel.

Our campfire circle assembled during 1954.

Nowadays the distance of 116 miles between Sierra Madre and Johnson Valley can be traveled in two hours. Not so in 1954. Providing one did not stop along the way, a minimum of three hours was required. The 26 miles of dirt road connecting Lucerne Valley and Johnson Valley were known as “the county road.” It ran between Lucerne Valley and Yucca Valley, a distance of 52 miles, and was replaced by State Route 18 in 1957, which became State Route 247. The road passes through Johnson Valley, connecting SR 62 in Yucca Valley to Interstate 15 in Barstow. SR 247 was designated by the California State Legislature in 1969; the county roads along that route were given to the state in 1972. Portions of the original county road still exist, and old-timers now call it “the old county road.”

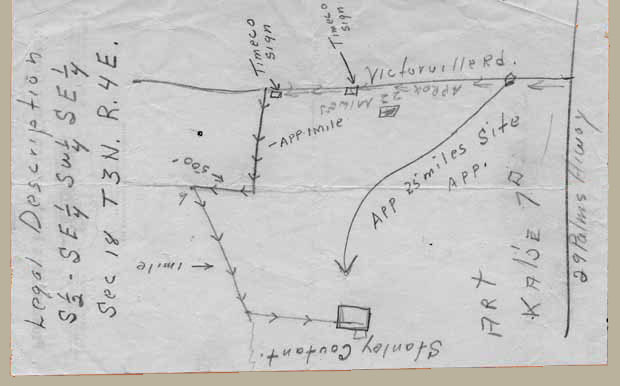

The directions we were given.

Fortune has smiled upon us many times during our desert adventures, and this first trip was one of them. We found a mining road angling off from the county road that headed toward the spot where we wanted to go.

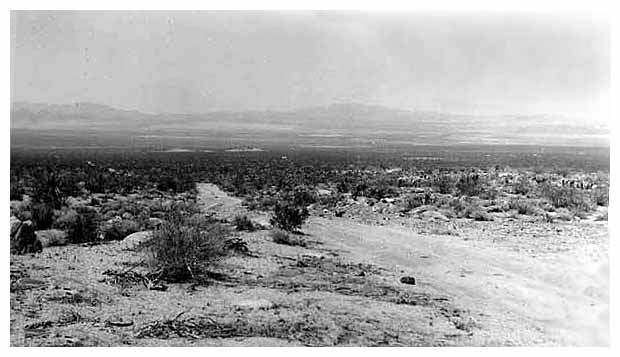

Looking north along the old mining road.

We stopped at what seemed the right spot according to the directions we had been given. After some searching, we found some BLM section markers. I was surprised someone had come out to the middle of the desert and stamped numbers into a small brass dome that was fastened to a steel pipe driven into the desert floor. How did they know where to put them? At the time I was eleven years old.

A pencil rubbing of a benchmark we

found near our property during 1954.

My dad was excited, as we had found the southern boundary of “Section 18,” whatever that meant. We were standing in Township 3 North, Range 4 East of something called the San Bernardino Meridian.

A 1951 cadastral discovered by JV property

owner Richard while out hiking during 2021.

Learn about the cadastral

More about the cadastral

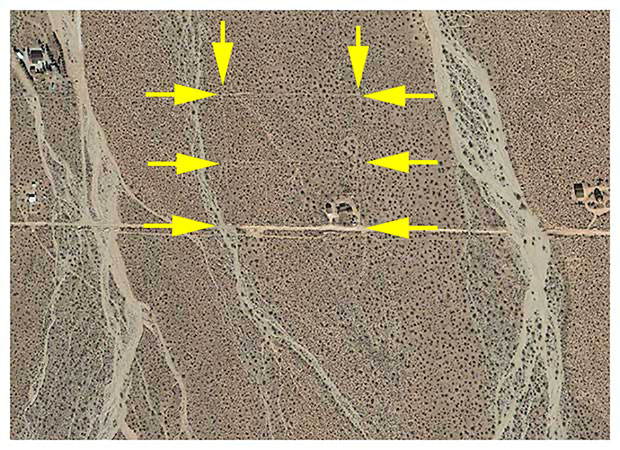

Five-acre parcels are 330 by 660 feet. In the vast desert that doesn’t seem like much. In town, it would be a huge lot for a house. We paced off the distance. We found a spot we liked between two washes. My dad speculated that if we bought and built on this spot, any future runoff would miss us. He was absolutely right, as we have since observed more than once during desert flash floods.

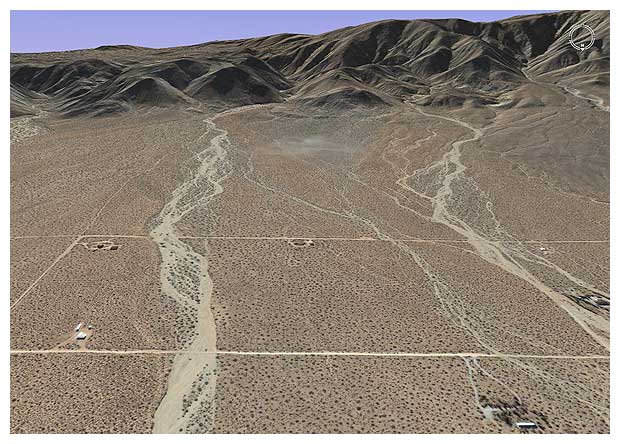

Our property is at the center. Washes flow on both sides.

Arrows indicate two rectangles outlining our parcels.

We realized we were on the border of the homestead parcels on the uppermost part of the slope. Providing the BLM did not open the land to the south, we would have an unobstructed view of the mountains. This turned out to be what happened. The federal government later declared the land between our land and the foothills a wildlife preserve. We were a mile from the county road, as remote as we could be.

Our house is located at the center. We are

looking south at the Bighorn Mountains.

As it turned out, when the new paved highway was constructed in 1957, it bypassed the county road, doubling the distance between our lot and the major thoroughfare to two miles. We accepted this as a plus, as it enhanced our remoteness.

In the weeks that followed we returned to the BLM office and put down our $25 filing fee for the south half of the southeast quarter of the southwest quarter of the southeast quarter of Township 3 North, Range 4 East. We had filed on a piece of the Mojave Desert. Marshall and Clara filed on the five-acre parcel alongside ours.

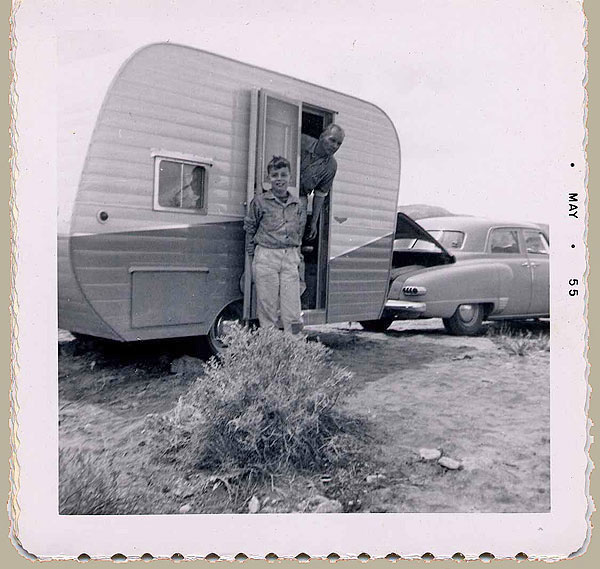

For the next three years we headed out of town on Friday night to visit our desert property, and returned to Sierra Madre Sunday evening. Like it or not, we had become “week-enders,” a term the then-few permanent residents inflicted on newcomers who still lived and worked “down below.” We had a 15-foot house trailer that we would pull with the Studebaker and park alongside the old mining road. It was a pleasant quarter-mile walk among the creosote and bladder pod bushes to our five acres.

The two Stans and the family trailer.

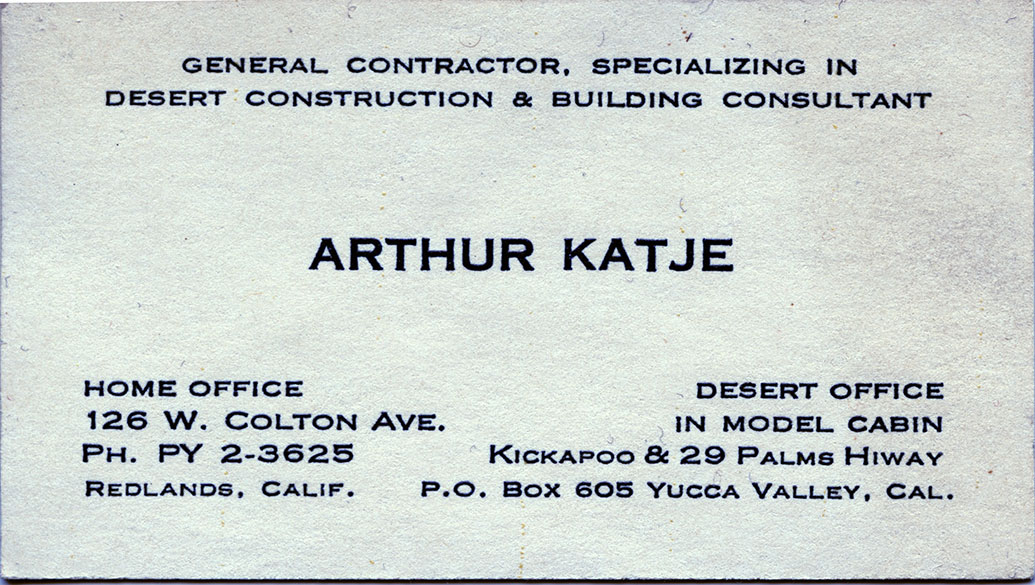

During 1957 we decided to hire a builder. We traveled to Yucca Valley and met building contractor Art Katje in his model home alongside the Twentynine Palms Highway. He agreed to build us a one-room cabin with a combined water tank house and bathroom on a concrete slab. One porch was included in the cost, but because our cabin was the first to be built in Section 18, Mr. Katje wanted it to be a showplace to attract other customers. He asked us if he could add a second porch on the opposite side of the cabin at no extra charge. Of course we said yes.

Today in Yucca Valley the street called Katje Way marks the spot where Art’s model home stood on the south side of the highway. Art pronounced his last name “cagey.”

Our lot number was 118, something my dad considered a good omen: “First in Eighteen.” And we were. The brass 118 marker now hangs above a doorway inside the house.

Because neither the county road nor the mining road reached our parcel, a man with a tractor was hired to cut a new road so Mr. Katje and his crew could reach our building site. This became Cholla Road, and remains as such today.

A man with a tractor helped make

it possible to begin construction.

We visited our land every weekend during this time, anxious to see what the builders had accomplished during the week.

January 3, 1957. Stan and Martha

warm up as I take the picture.

First came the footings and forms for the concrete slab, along with the rough plumbing. We noticed an identical set of footings had been dug on the parcel next to ours. Neighbors already? Nope. It turned out Katje’s men had started to build our cabin in the wrong spot!

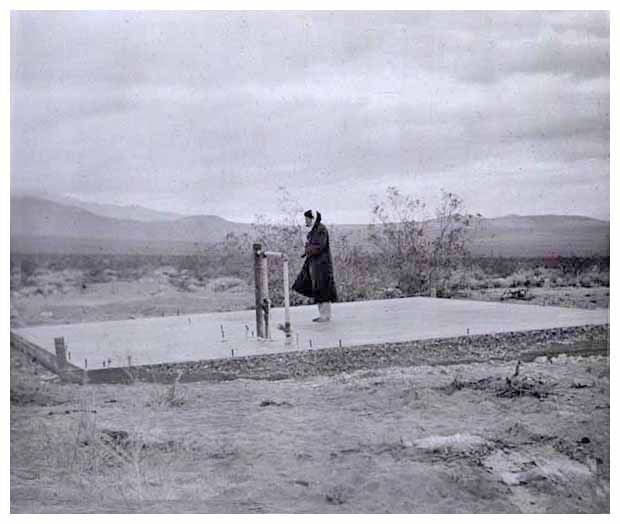

While admiring the new slab, Martha

protects her ears against a cold wind.

One cold, windy Saturday morning we arrived, anxious to see what had evolved during the week. My mother did not have a scarf with her, so she took a long, white strip of cloth and tied it around her head to protect her ears. What a thrill to find the slab had been poured!

Martha gazes westward while I take pictures.

Notice the wind blowing my pant leg.

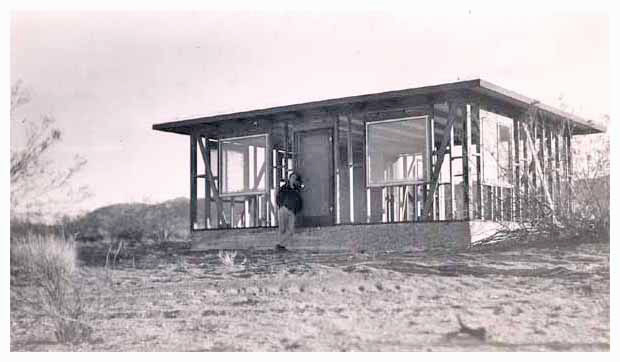

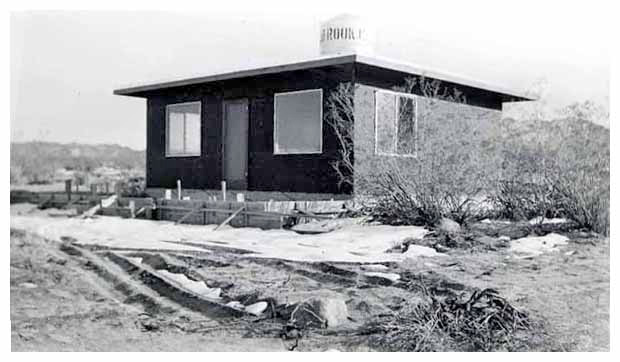

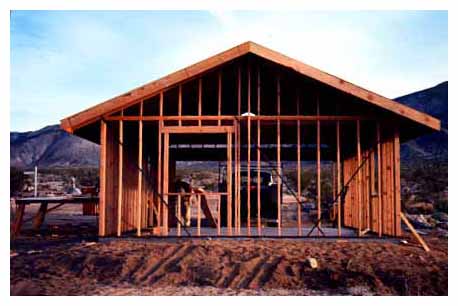

During the weeks that followed, the walls were framed, Celotex was added with hot-mopped tar on top for a flat “shed” roof, windows were set, and the backing wire, black paper, and stucco mesh wrapped around the outside of the walls. One weekend all was “chicken wire;” the next our house had beautiful yellow-buff stucco walls and a white “snow coat” roofing on top of the tar. The snow coat, which looked like thick white paint, lasted for several years, but eventually flaked and blew off in huge chunks that littered the desert around our cabin. We picked up what we could. Fifty years later I occasionally find a small fragment in the yard.

January 19, 1957: The cabin is framed.

February 3, 1957: The cabin is wrapped and ready for stucco.

Forms are set for the north porch, a gift from Mr. Katje.

Yes, that is indeed snow on the ground.

Later the same afternoon, from the southeast.

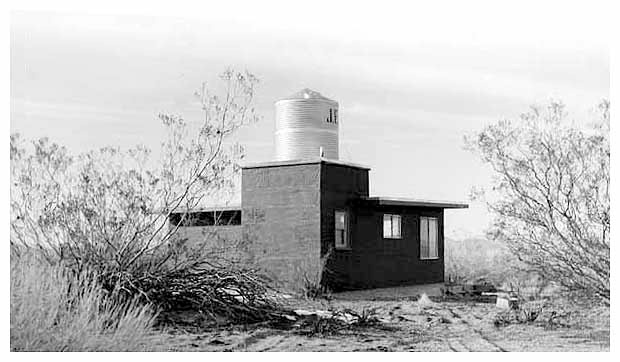

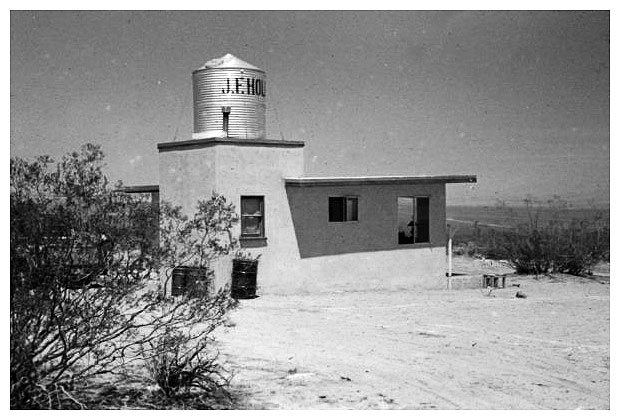

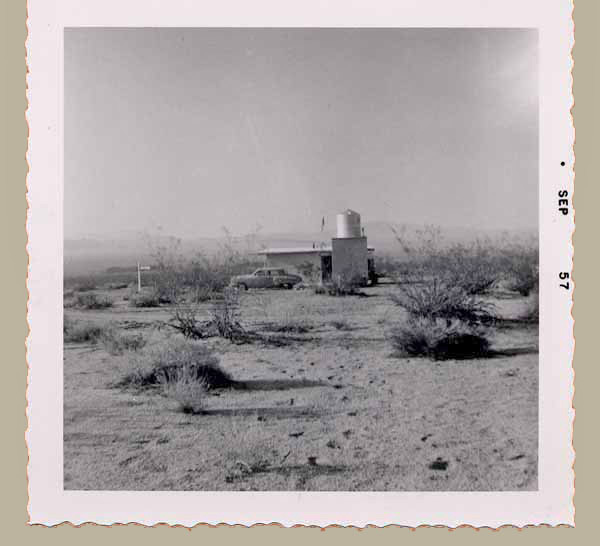

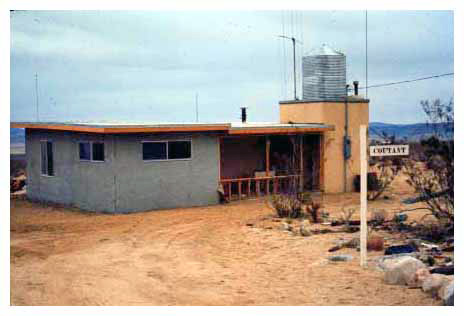

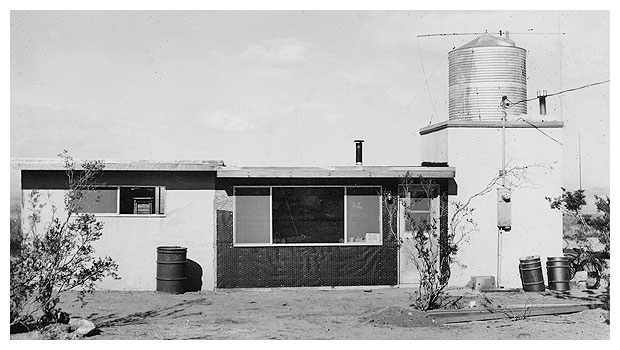

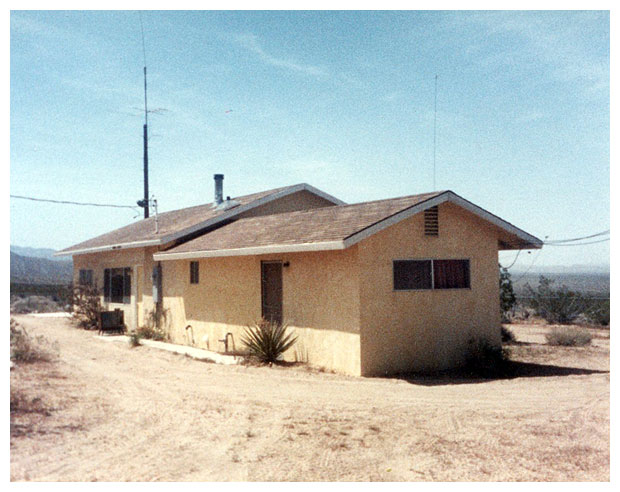

The original cabin is finished.

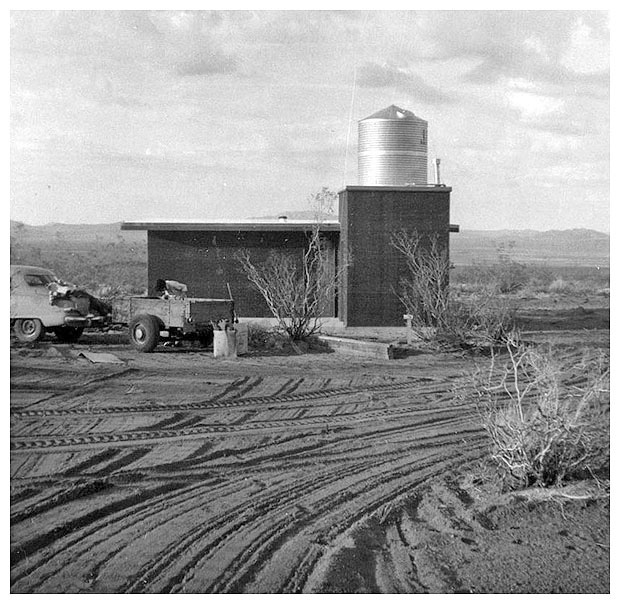

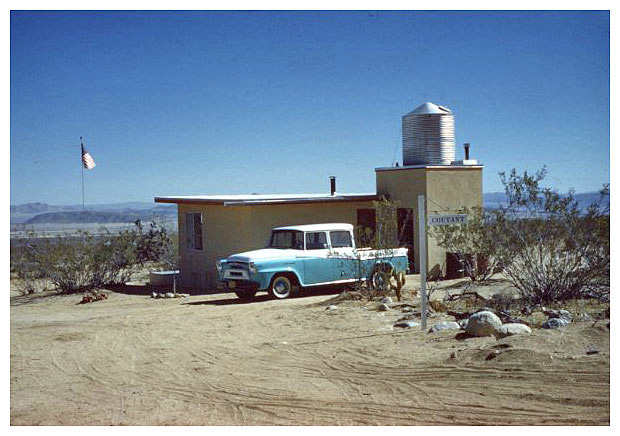

The bathroom is an 8-foot-square, 12-foot-tall structure at the southeast corner. Also it is the tank house. With closely spaced 2×12 rafters, it was designed to support a thousand-gallon water tank, which provided a low-pressure gravity feed domestic water system: seven pounds when full. When it ran dry, we would leave a message in Lucerne Valley for the water man to bring us a load.

We soon added a Kenmore kerosene water heater from Sears-Roebuck. One had to monitor it closely. If left unattended, the water in it would boil, and shoot up through the pipes into the roof tank. Then one waited for the water heater to cool, refill, and start over.

First in Eighteen, looking due north. Stuccoing is complete.

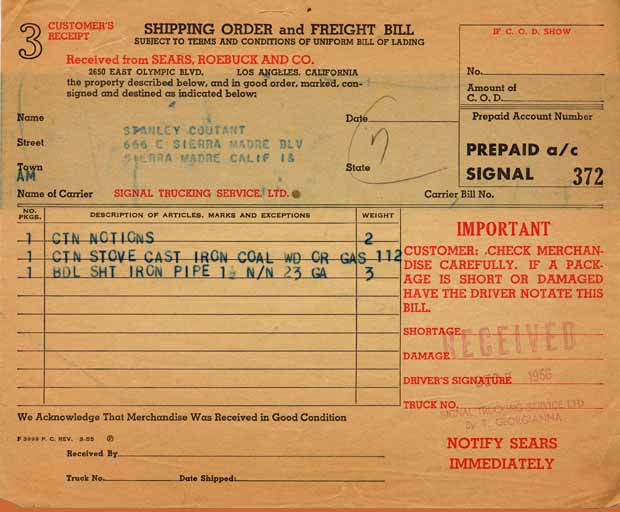

Just before Christmas of 1957 we bought a cast iron pot belly stove, also from Sears. It sat in its wooden crate on our front porch in Sierra Madre over the holidays. In my mind I can still see rain water dripping off its spherical shape, and I remember wondering if we were going to get it out to the cabin before it rusted. We did, and it served well as our wintertime heating source.

Packing slip for our pot belly stove.

An abundance of hot air has been produced

over the years by this marvelous device!

Do you have a stove like this? Need its booklet?

You can download its Operating Instructions and

Parts List (at 16.5 megabytes), 8½ × 11 inches.

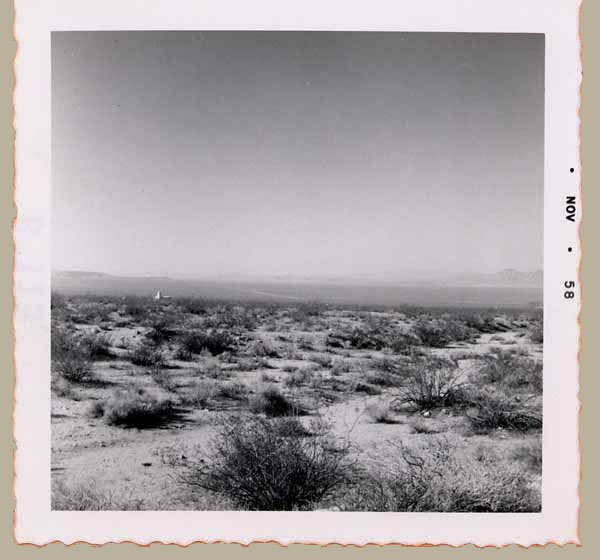

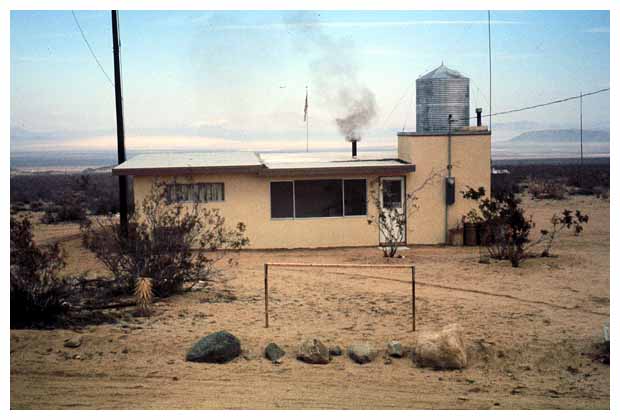

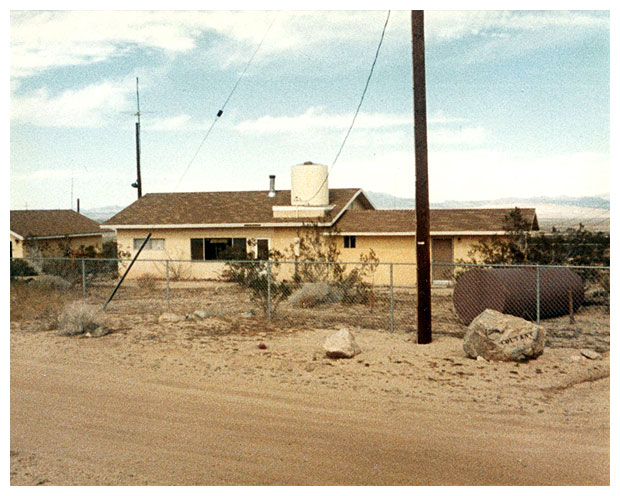

Definitely a remote location. We are looking west-northwest,

toward Lucerne Valley. Our water tank reaches for the sky.

By this time it was November of 1958. At this stage we were set. We had a kerosene water heater and kerosene lamps, running water from the tank on the roof, a Coleman camp stove for cooking, and a wood-burning stove for heating. There was no electrical utility service available for over 20 miles, but we didn’t care. We had our own desert cabin!

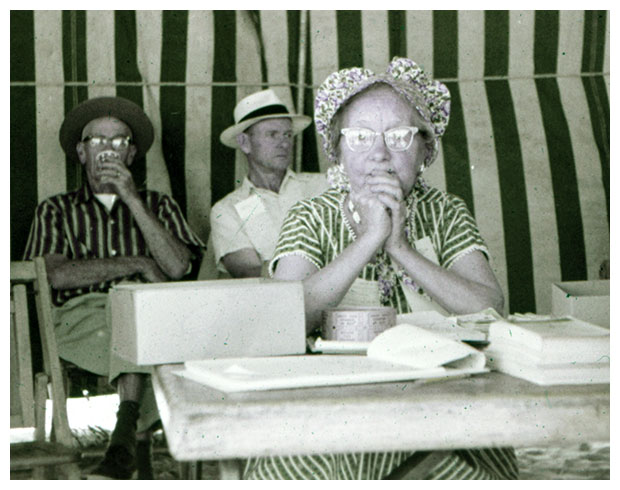

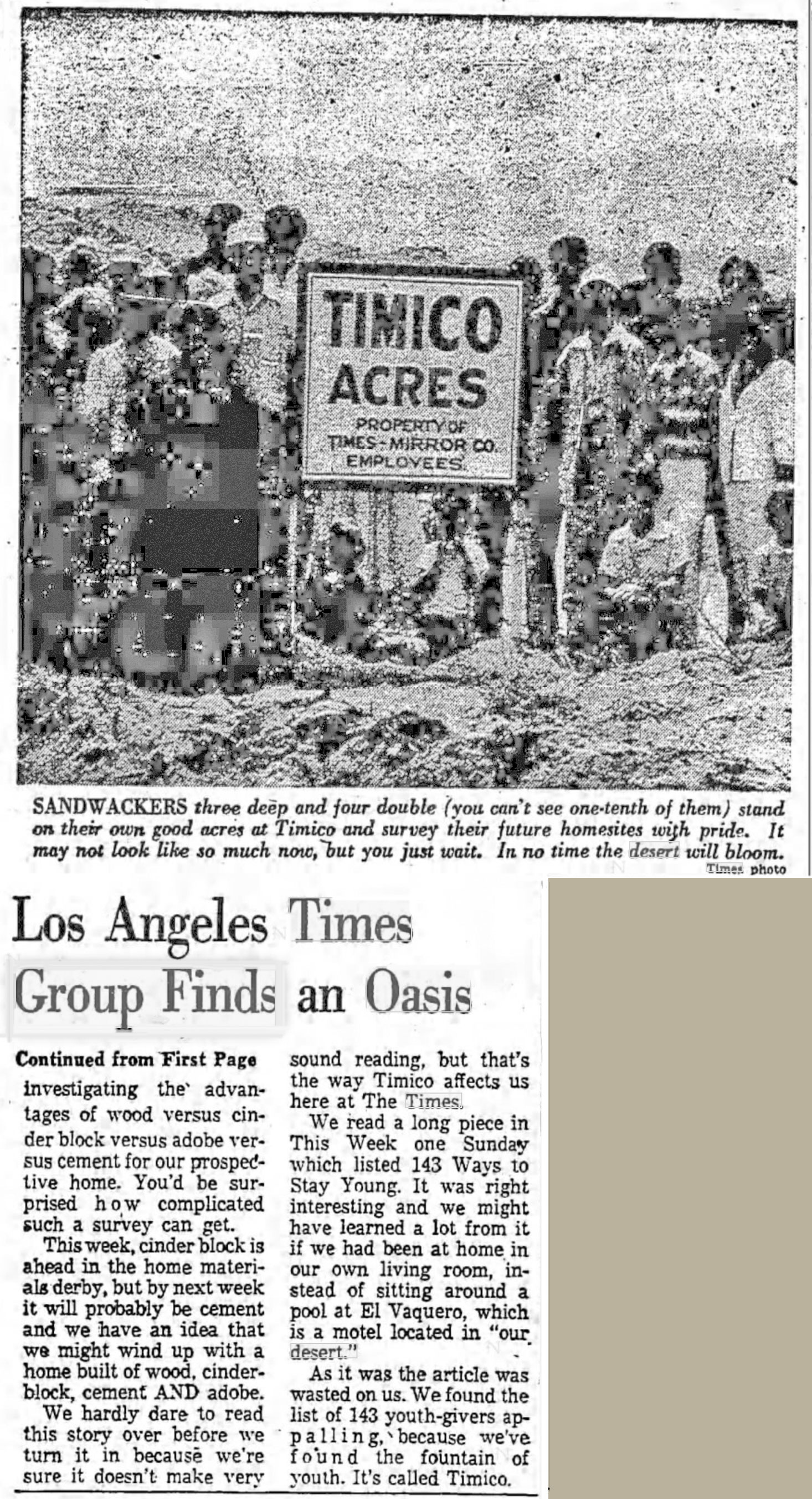

Secretary Irene Miller at the TIMICO Acres

property owners registration tent.

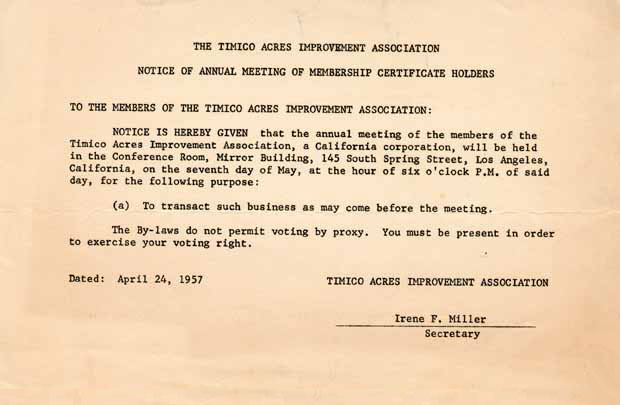

A property owners meeting announcement.

A June 17, 1957 clipping from the Los Angeles Times.

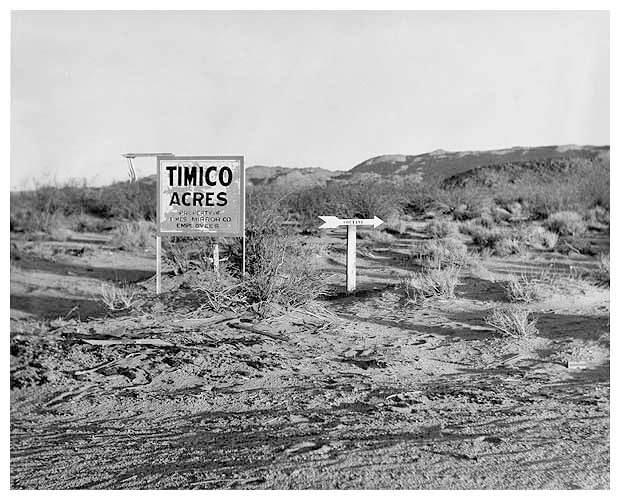

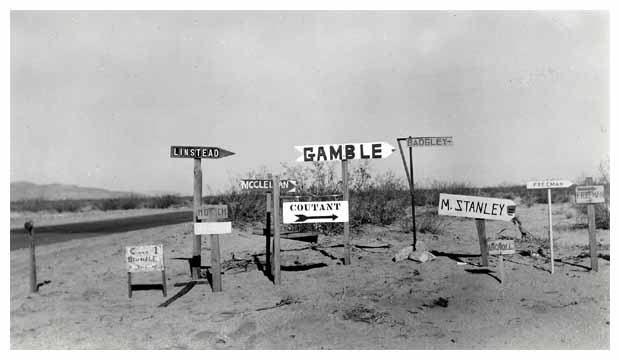

Employees of the Times-Mirror Company who owned desert property formed an association named TIMICO. Sections 7 and 18 became TIMICO Acres. Homesteaders were assessed and roads were put in so that each property owner had access to his five-acre parcel… except for Marshall and Clara Annis.

The first signs of civilization in TIMICO Acres.

The white arrow is stenciled “COUTANT.”

As it turned out, the other homesteaders had chosen to orient their parcels with the 660-foot length running north-south. Not realizing what this would mean later, the Annis and Coutant contingent chose east-west. Our parcel ran alongside the road. The Annis parcel was marooned.

There was no road to the Annis abode.

Another man with a tractor was hired, and added what became known to the five of us as “Annis Avenue” along the east edge of our property. Clara said “Annis Alley” seemed more appropriate. Now Marshall and Clara could drive to their parcel, and soon towed an old green house trailer there, put it up on blocks, and removed its wheels. Marshall built an outhouse out of two-by-fours, plywood, and corrugated siding for the roof, with a vent made of stovepipe.

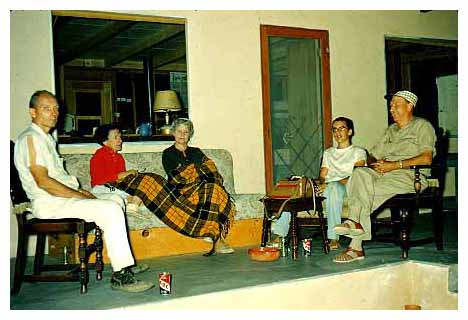

Stan, Martha, Clara Annis, yours truly,

and Marshall Annis in May, 1959.

Marshall and Clara never developed the JV property. Instead, they bought a lot in Hesperia where they constructed a home. During 1975 they sold us their Johnson Valley parcel, which pleased us immensely.

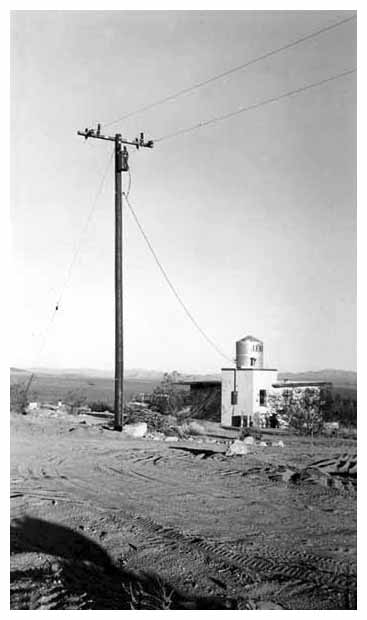

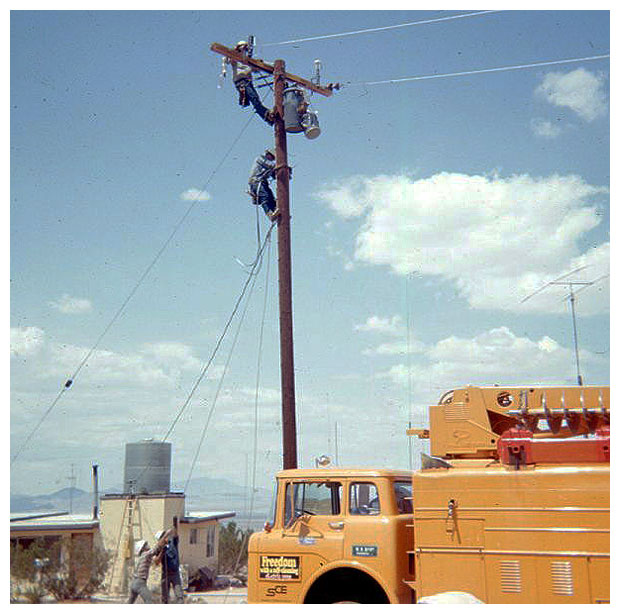

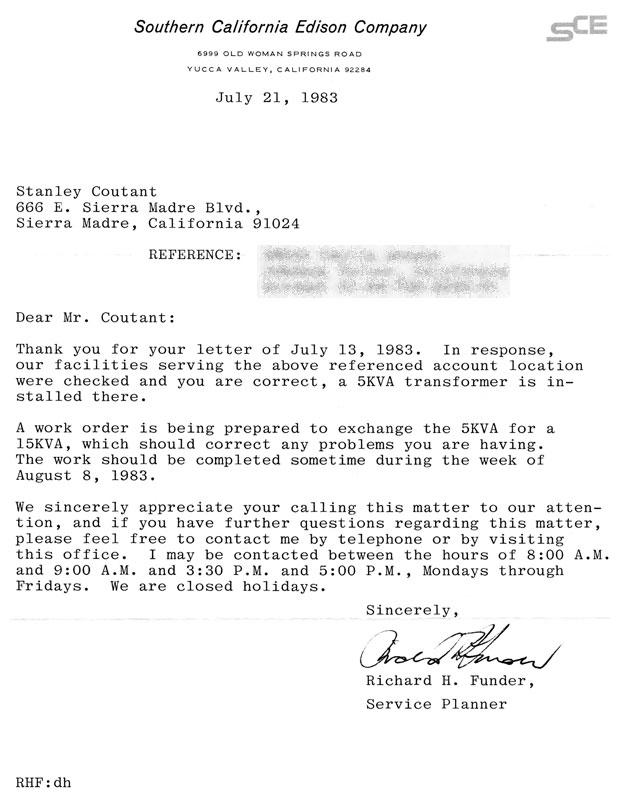

An amazing thing happened in 1959. Someone at the Cal Electric Power Company in Victorville decided to extend the existing service beyond Lucerne Valley, and our house was to be at the end of the line. New poles appeared, marching east alongside Highway 18, abruptly turning south at the road leading to our property.

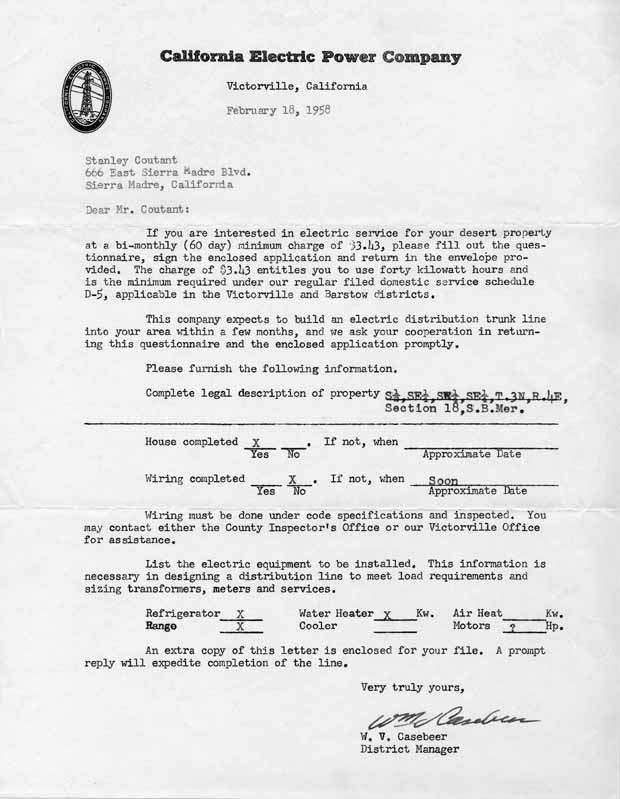

An intriguing letter from Cal Electric.

The last pole was set in place near the corner of our parcel. It was almost too incredible to believe. We had 120/240-volt commercial power! Not only that, we were the lone customer on a 20-mile line. With guidance from Marshall Annis, who was a journeyman electrician, my dad and I wired our cabin. Except for one short in a kitchen receptacle, which we fixed, the new wiring worked perfectly.

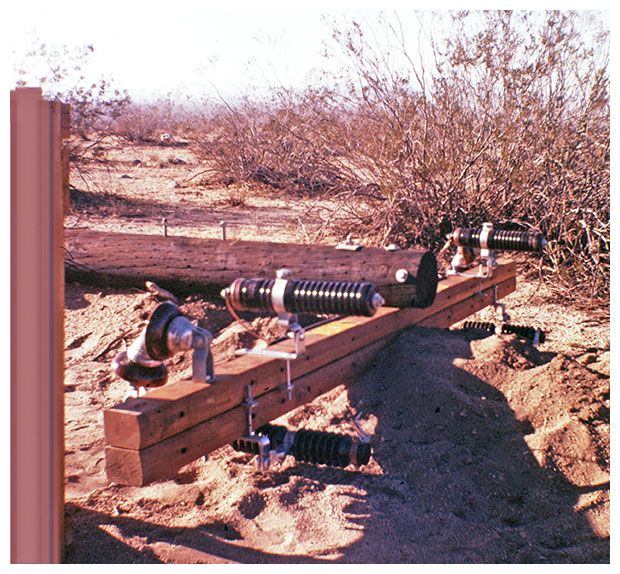

Along with a pole, our new pole pig transformer arrived in a crate.

We were first in Section 18 to get commercial power.

What a thrill.

As the years passed, other property owners had cabins built and signed up for power, but many were a parcel or two from the pole line, and had to pay for a connection. $2000 each was about average for the extra poles and wires required. Some neighbors were angry when they learned the line was brought to our door yard at no cost to us, but got over it when they realized someone had to be first, and that it was only logical the power company wasn’t going to run a new line to an uninhabited spot. Fortune had smiled upon us once more.

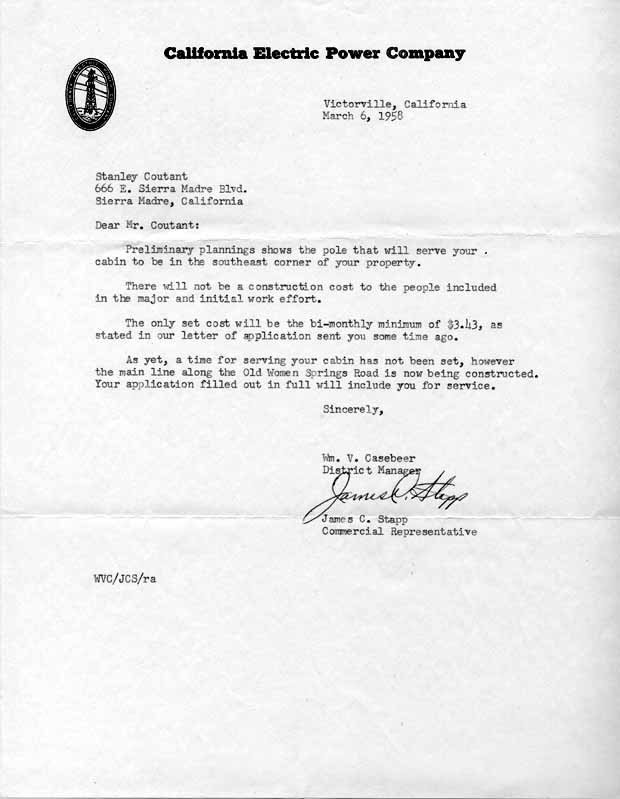

Another letter from Cal Electric.

Over the years Cal Electric was bought by the Southern California Edison Company, which continues its now vastly expanded service to Johnson Valley via a new line from Yucca Valley. The original line from Victorville still exists as a backup, and according to a friend who works for Edison, the switch that must be thrown to make the change-over is at the north end of Bighorn Road.

Eventually the original Cal Electric 5 kVA power transformer became

inadequate, and in 1983 was replaced by one with a 15 kVA rating.

Also in 1959 my dad replaced the Studebaker

with an International Harvester “Travelette.”

At the corner of Bighorn Road and Highway 247

when it was simply Old Woman Springs road.

During 1958 I spent the summer with Clarence and Ina Goodridge. “Goodie” was a builder, and asked if I would like to spend time with them and in the process learn about construction. It was the beginning of a friendship that lasted until his death in 1995. I spent the next six summers working for Goodie building cabins on the desert or at Big Bear. This included everything from setting forms and digging footings right up to putting on the roof. Goodie did not like electrical work and I didn’t like plumbing, so he worked with the pipes and I did the wiring, and we got along well. I also learned to use Goodie’s various tractors, which I thoroughly enjoyed.

I enjoyed operating Goodie’s Case tractor.

We dug foundations with Goodie’s Minneapolis-Moline tractor.

Ina’s home cooking was world-class, and we ate well. I lived with the Goodridges each summer. The first year I worked for my room and board. The next five summers Goodie paid me, explaining that I had learned enough to share in the profits. Mornings and evenings we milked Ina’s goats named Frosty and Ruth Ann. On weekends we rode their horses named Buck and Holly. We also dragged roads and delivered water, two of my favorite tasks. During the sixties Goodie built a swimming pool, which was a favorite place to be.

A sad update: Ina left us on Tuesday, July 7, 2009.

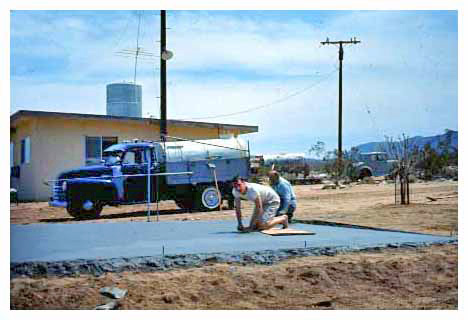

One of my favorite jobs was delivering

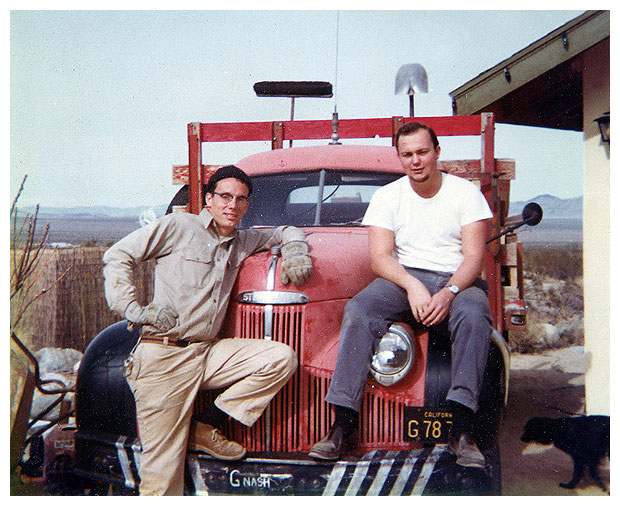

Adam’s Ale with Goodie’s water truck.

My cousin Pete is on the right.

Sometimes Goodie would hire extra workers. When he did, I was assigned to take one of his trucks to the Gibson Lumber Yard in San Bernardino for a load of building material. I would leave at sunup and get back to the desert at sunset.

The lineup: Goodie’s trucks and my Model A Ford.

During one of these journeys I was eastbound at Old Woman Springs when I noticed a blue Volkswagen beetle headed west. There is little traffic on desert roads; it’s difficult to not notice every car one sees. Its occupants were wearing dark glasses as they faced the setting sun. They looked familiar. In fact, they looked like Mia Farrow and Frank Sinatra.

While in town a day or two later I overheard a fellow telling his friend how he had stopped to help two people in a blue VW with a flat tire. He said it was Sinatra, and that Mia had wandered off a short distance into the desert and appeared to be admiring the scenery. This fellow said he changed the tire, and that Frank gave him a $50 bill for his trouble.

Shortly thereafter I learned that Frank and Mia were married in Palm Springs, and from there headed off on their honeymoon. I had been in the right spot at the right time to see them. Sadly my memory of the day has lasted longer than their marriage.

Update: Frank and Mia were married on July 19, 1966, and according to what I have just read, the ceremony was in Las Vegas rather than in Palm Springs. Nevertheless, they did pass through Johnson Valley on the day that I saw them. There is no doubt in my mind on that point.

Citizens Band radios played a role in Johnson Valley from 1959 until telephones arrived ten years later. A number of permanent residents set up CBs, which were used not only to stay in touch, but also served as a means for summoning aid in an emergency. Two original users were Daisy Crawford, 11W6892 and the Goodridges, 11W9463. As the week-enders learned about the value of a CB set, antennæ appeared on Johnson Valley cabin roofs. We applied for a license, and were issued the call letters 11Q0318. It was one big friendly party line.

During this time the nearest telephone to our desert abode in Johnson Valley was 26 miles away in Lucerne Valley. It was that year a fellow with the unlikely-sounding name of Purky bought a parcel and built a 12×12-foot shack on it. He lived in Alhambra, and was a desert weekender.

“Purky,” perhaps “Perky;” I never saw his name written down was retired from a company where he had been an electronics technician. He drove a black Ford Ranchero with a big V-8 in it. He enjoyed Christian Brothers Brandy, and would consume a capful (cap full?) every now and then as the day and evening wore on.

He was old and skinny in my eyes; I was 15 at the time so he could have been 65 or so. He had built his own CB transceiver he had named “The Block Buster,” and wanted to introduce the Citizens Radio Service to the rest of us desert rats, and invited my dad and me to visit him in his small cabin. “I thought it might be smart for a few of us to get involved with CB radio,” he explained. “We can use them to stay in touch, and there may be times when it’s urgent.” He got that right.

We ordered two Heathkit transceivers, which I assembled. The transmitters were rockbound, but the receivers were tunable. Twenty-three channels were available. As per Purky’s recommendation, we bought crystals for channels 7 and 11 in the 27-megahertz (eleven-meter) band. These were five-watt AM rigs equipped with vacuum tubes. Other manufacturers of factory-built rigs included Gonset and Globe; eventually Citi-fone, E. F. Johnson and Philmore got involved. Lafayette and others brought out solid-state rigs; eventually synthesized and single-sideband 40-channel equipment became available when the Commission expanded the band.

CB played a role in our lives until telephones arrived during the seventies. Over the intervening years various emergencies occurred, and our CBs were used to summon aid.

Talking about schematics with friends inspired me to share this story, because nowadays we hear them called “circuit diagrams.” The word “schematic” brought back these memories, including one about another old man named Maury, who lived halfway between Johnson Valley and Lucerne Valley. He had a CB, and called the diagrams “screed-o-matics,” which tickled me. As far as I know, no one ever corrected him. (Why spoil the fun, right?)

Maury had a collinear vertical. It worked well; he called it his “colonial” antenna. One breezy morning he was not hearing another station well, and observed, “I guess the wind is blowing your signal the wrong way.” These were fun times when CBs were vital to our convenience and safety.

The Citizens Band Radio Service (CBRS) is under the auspices of the U.S. Federal Communications Commission, Part 95 of its rules and regulations. Citizens band radio (CB radio) is a land mobile radio system, a system allowing short-distance one-to-many bidirectional voice communication among individuals, using two-way radios operating near 27 MHz (or the 11-m wavelength) in the high frequency or shortwave band. Citizens band is distinct from other personal radio service allocations such as FRS, GMRS, MURS, UHF CB and the Amateur Radio Service ("ham" radio). In many countries, CB operation does not require a license and may be used for business or personal communications.

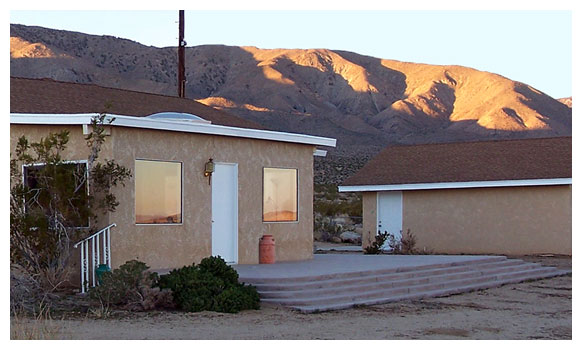

April of 1962 saw the addition of two bedrooms on the west end of our cabin. Goodie and his helper Dick Meeks did the work. They enclosed the back porch at the same time, in effect giving us three new rooms which turned our cabin into a house. No longer were we compelled to go outside to get to the bathroom, a great relief on cold, windy nights.

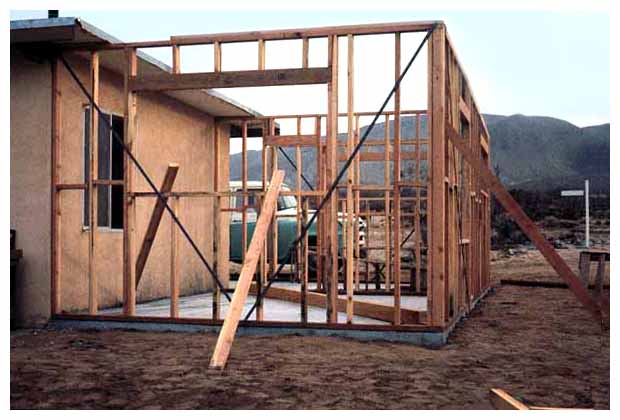

An extension of the slab flooring is added

to accommodate two new bedrooms.

Looking south at the new bedrooms

with the Bighorn Mountains behind.

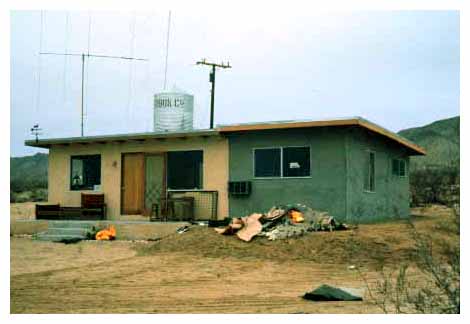

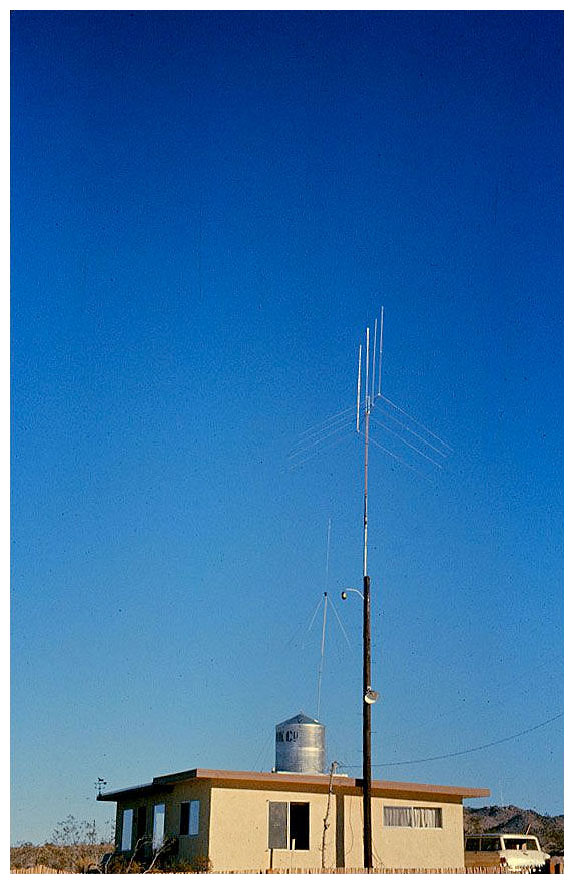

Looking slightly north of due east. To the left of

the water tank is a four-element CB antenna.

Looking due west toward Big Bear.

The new bedrooms are stuccoed, but the south porch is open.

We decide to enclose the porch as well.

A better view of the CB antenna.

April, 1962: The two new bedrooms are completed.

We added a utility pole to support the CB antenna.

The south porch is enclosed. We are looking north.

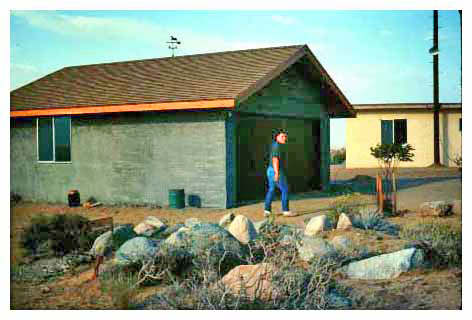

During the month of August, 1980, it was decided to add a gable roof to the cabin. Upon the recommendation of friends Fred and Paulyne Mayes, Bill Lee, a Yucca Valley building contractor, was hired. He and his crew constructed the new roof—including the front porch—in less than four days. The following week Darrel Samuels, a painter from Yucca Valley recommended by Mr. Lee, painted the new roof overhang, the gable ends, the new front porch, and the overhangs of the garage and ham shack. This was accomplished in one day with spray gun equipment. The same day he painted the inside of the back porch using conventional roller and brush methods.

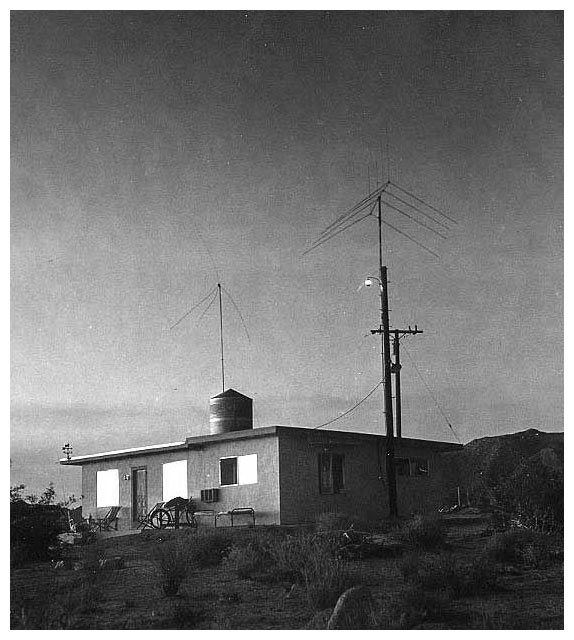

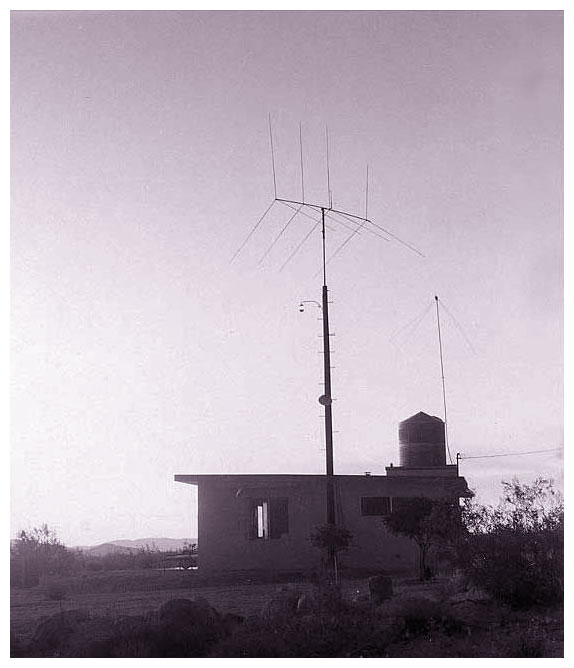

The Gizmotchy and the ground plane.

The Gizmotchy is the taller of the two.

Yes, on this day in 1962 the sky was that blue.

Immediately after acquiring our CB radios, my dad and I began to experiment with a variety of antenna designs. The Utica Radio Corp. had introduced the “Gizmotchy” in 1960, and we decided we had to have one. For the technically inclined, it is a circularly polarized directional antenna with a forward gain of approximately 12 dB and a front-to-back ratio of 28 dB. Enough of that kind of talk; there may be women and children present. One reason for having the two antennæ is that the ground plane is non-directional, or “omni-directional,” making it well-suited for communicating with most stations in a specific area. The Gizmotchy is “uni-directional,” in that it transmits toward and receives from the specific region in which it is pointed. This makes it ideally suited for communicating with a certain locale, often over greater distances than are possible with a ground plane antenna. For example, if we wanted to contact a station in Lucerne Valley, we would point the Gizmotchy northwest, and have a better chance of getting through, as the Gizmotchy type of antenna focuses all the power in one pathway, plus it receives signals from that area better, and tends to reject signals coming from other directions. This explains why the generic name for this type of antenna is “beam.” There are other designs of beam antennæ besides the Gizmotchy. One popular type is the Yagi-Uda. Another is the cubical quad.

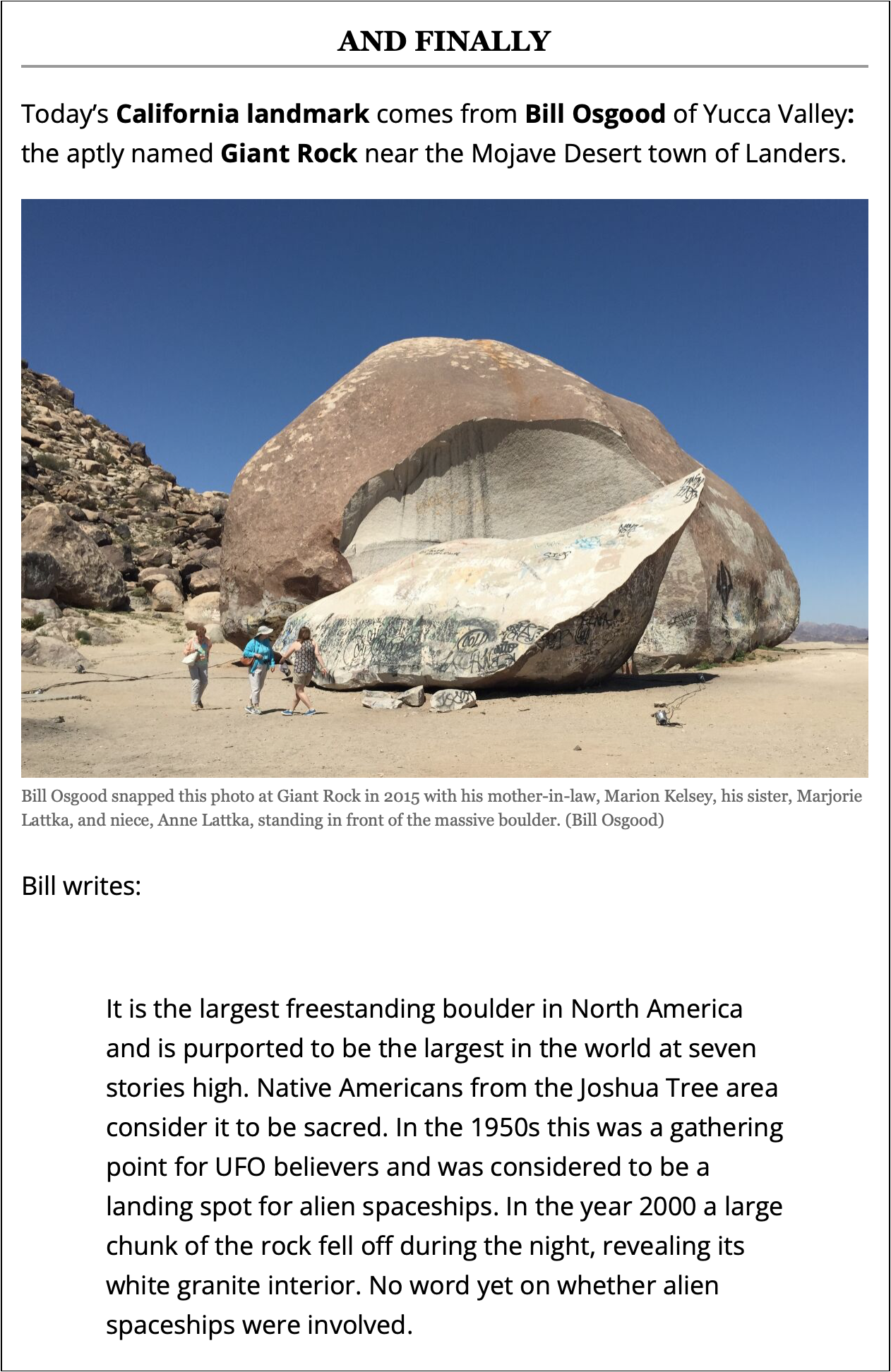

While on the topic of intensely blue desert sky, here’s a 2023 news item from The Los Angeles Times about Giant Rock near Landers, located 15 miles southeast of our homestead.

A Johnson Valley jam. Martha is closest to the camera,

then Cousin Pete, Cousin Flo, and me on the organ.

In 1965 my dad and I built a two-car garage to the west of our house. A workbench was included so we could move our tools and projects out of the house. No longer did our car have to sit outside all weekend regardless of the weather. Here are five views of our progress, beginning with the site preparation and ending with the preliminary coat of stucco:

Several Polaroid prints were found showing details of the garage

construction. After viewing, return to this page to continue.

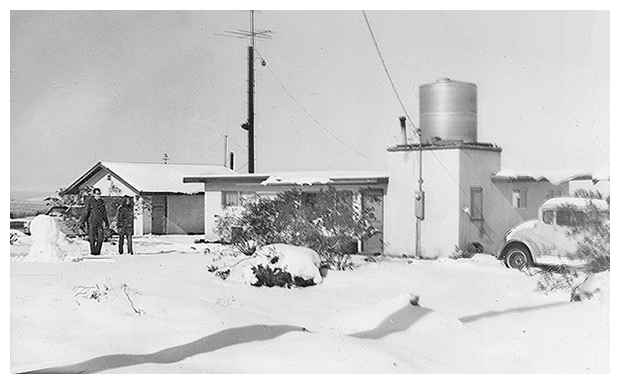

“The Big Snow of February, 1968.”

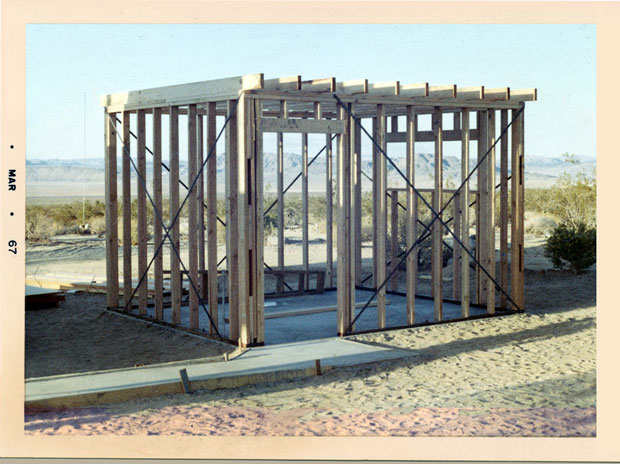

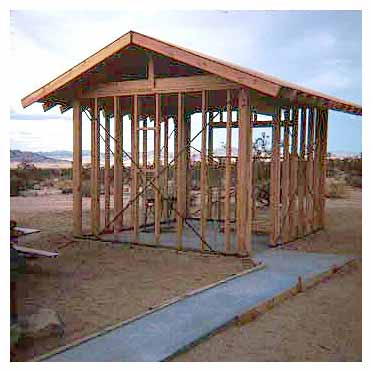

My dad and I became interested in Amateur Radio. It offers a greater range than CB. He was granted the call sign WA6BLK. Mine was WB6WFI, and is now AA6SC. In 1967 we built a radio room, our “ham shack,” fifteen feet east of the house. This got the radios and their sometimes obnoxious noise into a room of their own, much to the relief of all. We intentionally aligned the ham shack with the house, planning for the day when we would join them. For those interested in details of our desert ham shack, a separate page is available. Use your BACK button to return to this page. https://www.coutant.com/aa6sc/index.html

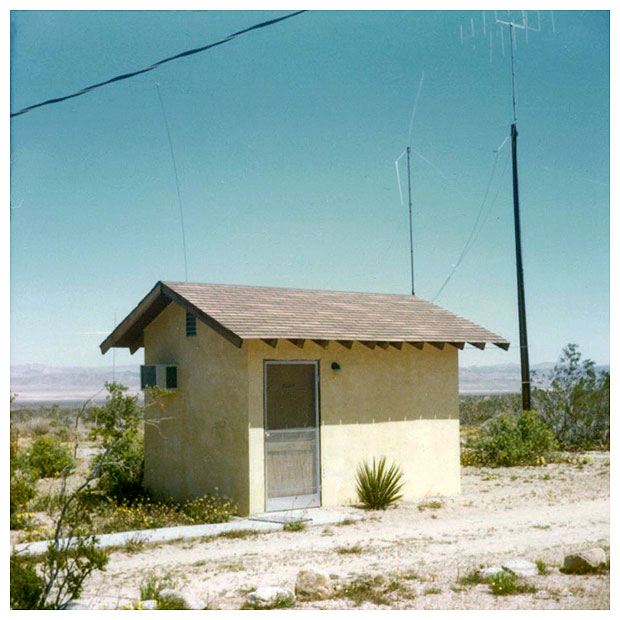

1967: We build a ham shack adjacent to the house.

The new structure is finished. Radio

noise is no longer heard in the house.

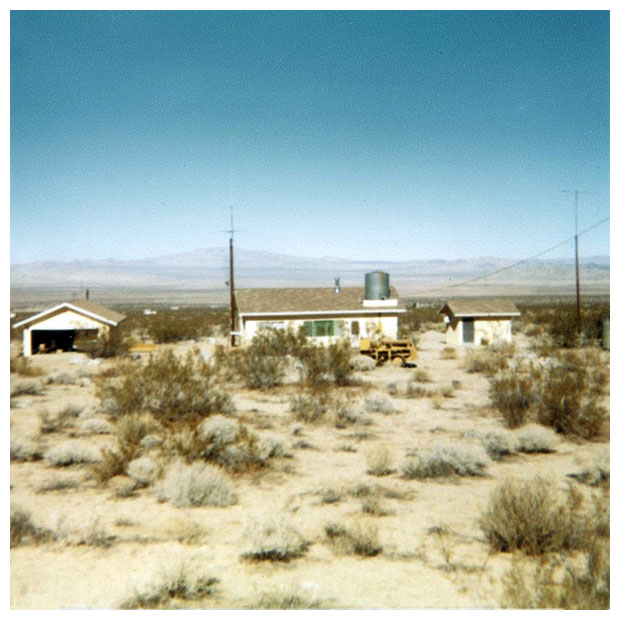

The Ham Shack stands alone at the right; the garage at the left.

1981: The decision is made to construct a utility

room between the house and Ham Shack.

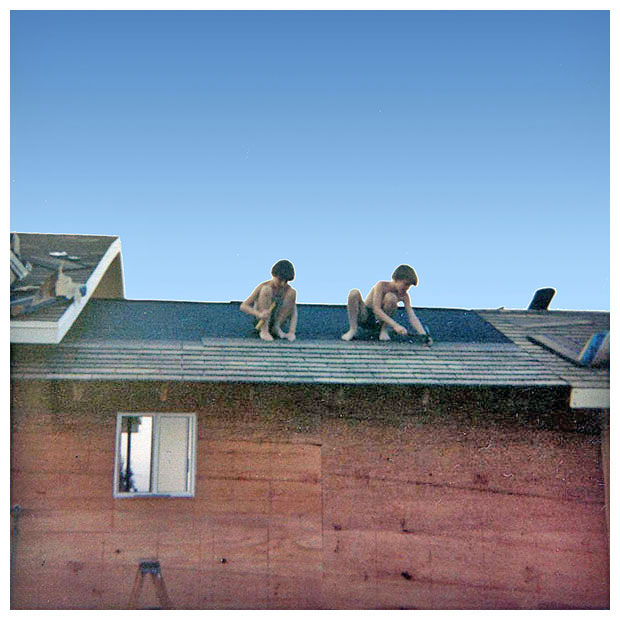

Sons David and Jonnathan apply shingles to the utility room roof.

David decides the new room is to be known as the Cram Shack.

Stan O., Clarence “Goodie” Goodridge, and Stan spread stucco.

A minor update: Invoices have been found indicating dates of purchase for utility room materials, including concrete for the slab, which was delivered on August 11, 1981. Lumber, plywood, drywall and insulation were delivered on August 18 and 20. Plaster sand for stucco arrived on Dec. 28, 1981.

Now only the garage stands apart.

The house, Cram Shack, and Ham Shack are contiguous.

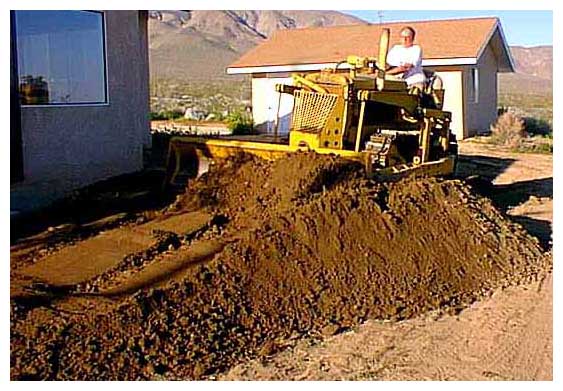

While working for Goodie during the late fifties and early sixties, I had noticed an old Allis-Chalmers Model M crawler tractor equipped with a bulldozer blade sitting next to a cabin about a mile east of the Goodridge house. Years before it had been used to level the site for the Community Hall, but it had not turned a tread since.

Because I so enjoyed operating Goodie’s tractors, and because the dirt roads throughout Johnson Valley to this day are maintained by residents, I thought it would be great if we could have our own tractor. We could take care of the roads around our place, and for me running a tractor still held its appeal. To the best of my recollection, the year was 1962. I made inquiries and contacted the tractor’s owner. Yes, she said, it was for sale at five thousand dollars. To me at age 19, it might as well have been all the money in the world.

Eighteen years later, in 1980, I contacted her again. She asked, “You still want that old thing? My first husband is gone. He’s the one who liked that tractor. My new husband has no interest in it. If you want it, you can have it for eleven hundred bucks.”

Our longtime friend Fred Mayes had been a heavy equipment maintenance foreman for the Hazard Construction Company for many years. He came out and looked over the tractor. “I’m surprised it’s in such good shape,” he commented. Having received his enthusiastic approval, I wrote a check. At last the tractor I had coveted for years was mine.

I had to drive it past Goodie’s house on the way home. He came out, beaming. “I’m glad you got that,” he exclaimed. “It’s a good’un, and you deserve it.”

1980: Sons David and Jonnathan in the tractor

the day it was brought to its new home.

A few days later I telephoned Allis-Chalmers in Los Angeles. “We don’t make tractors,” announced the young, slightly haughty feminine voice on the other end. “That’s funny,” I retorted. “I own one.” Finally she determined that I needed to contact the Superior, Wisconsin office. The Los Angeles plant makes only gravel-screening equipment, she said.

I called Wisconsin, and Fortune shone once more. “What’s the serial number of your tractor?” he inquired. I gave it to him. “Can I call you back?” he asked. “Sure.” I gave him my telephone number.

Twenty-five minutes later he called. “I have the original invoice for your tractor here on my desk in front of me,” he announced. “It was built in 1937, and is number ninety-five in its series. Would you like a copy of the operator’s manual for it?” You can guess my answer.

“Is it still running?” he asked. “Yes,” I replied. “Could you send me some photos and a write-up? I’m the editor of our company newsletter, and I’d love to publish a story about your Model M.” Eagerly I complied. Sure enough, about a week later a photocopy of the manual arrived, along with several beautiful color brochures for the current product line.

In case you are wondering, yes, the tractor still runs. As a matter of fact, Dixie can be seen operating it during 1991. It has what I suspect is an intake manifold leak that I hope to fix someday, which should give it back its full power. Even with this problem it’s a rugged machine. 2007 update: Neighbor Roger Taylor made me an offer I could not refuse. With some remorse I sold him my Model M.

1997: We add a porte cochère along the south side of the house.

Contractor Vic DiAco did a magnificent job, assisted by the

brothers Ray and Mel Dunn, along with Sharon Edwards.

1998: Adding a north porch. That’s my 1937 Allis-Chalmers crawler.

The new north porch is finished.

We’re ready for dinner guests!

The day we joined the ham shack to the house was during the summer of 1981. I could not fit beneath the original cabin’s overhanging roof and the lower roof of the new room, so my sons Jonnathan and David, who were 11 and 10, wriggled in and nailed down the shingles. When completed, David named the new room. He said, “If that’s the ham shack, then this should be the cram shack.” An electric water pressure system was installed there, along with a washing machine, a dryer, and a brand-new electric water heater. The water tank came down off the roof forever, and was relocated in the yard.

Here is a view of the ham shack, cram shack, house, and garage.

Many interesting things have happened in Johnson Valley during the past sixty-five years. Here are a few memorable incidents, not necessarily in order.

Daisy Crawford sold me her 1931 Model A Ford for $15. Soon I mounted bald tires all the way around and used it as a Jeep. With it I have pulled many people out of soft sand where they were stuck. Because I was the oldest kid in the valley and the only one with a car, many Saturday evenings were spent riding around with other kids squeezing in and on wherever they could: in the rumble seat, on the running boards, or straddling the front fenders.

The Model A Ford that I bought from Daisy Crawford.

I bought a real Jeep—a Willys CJ5-A, painted Indian ceramic. It could go places the Model A couldn’t, but it didn’t have the Ford’s charm.

Three families acquired parcels along an unnamed dirt road. They were the Goodwin, Ivers, and Norton families, so they named the road after their combined last-name initials. To this day, it is called Gin Road.

Joe DeVictoria, proprietor of the Chisel Inn, went on a shooting spree and killed his wife Aileen, her lover Jim Kirkendahl, and friend Marilyn Tiggeman. He also wounded Jim’s son, and Bill Kensinger, another friend. The Chisel Inn took its name from an old chisel that was found in the dirt while the foundation was being dug.

Many hours were spent riding four horses: Holly and Buck belonged to the Goodridges, Beauty to the DuMond family, and Robin, owned by a neighbor girl named Judy Roberts.

Holly, Robin, and me on a cold morning.

Good friend and fellow printer, Michael Patrick Shane Waite, visited me in TIMICO Acres several times and fell in love with the desert. He wanted to buy a place. We found one he liked. It had a cabin on it. He was short on cash, so we bought it together. Later Mike bought me out. Now he and his wife Linda live there along with their many animals, and Mike owns and operates the local livestock and poultry feed store in the region near Landers called Flamingo.

2010 update: Mike has retired from the feed store business.

2021 update: On May 12 something went terribly wrong while Mike was unloading a truck. He fell backward, striking his head in the process. He did not survive. We lost a dear and longtime friend. Rest in peace, Michael.

The 210 Freeway extension was completed in January 2003, and runs between the city of La Verne and Interstate 15. The newly completed section is shown above. One can travel non-stop from Sierra Madre to the Cajon Pass summit and beyond on freeways without touching Interstate 10. What a relief. We homesteaded our five-acre parcel in 1954, and have enjoyed it for sixty-five years.

February, 2006: Larrea Road is paved! I didn’t expect to see this in my lifetime. From Highway 247 to the Community Hall and fire station complex it is two lanes in width. From there to the church it is a single paved lane. Its overall length is slightly greater than two miles.

The south end of Larrea, looking north toward Highway 247.

At Ocotillo on Larrea, looking northeast at the Goodridge property.

Just south of Ocotillo on Larrea, looking south-southeast.

The north end of Larrea, looking south from Highway 247.

Highway 247 at Larrea. Lucerne Valley is 26 miles to the west,

while Yucca Valley is 20 miles to the southeast.

Update: Martha Wood Coutant died at noon on September 12, 2013 at the age of one hundred years and eight months. While going through her papers on Sept. 29 we found she had written the following epilog, which she entitled, “A Little More of the Saga.” In it she refers to my father as “Stan,” and to me by my childhood nickname, “Stano.”

It should be noted that S. O. Coutant was too modest in his report on “The Saga of Our Very Own Johnson Valley.” His mother is taking care of that at this moment.

Stano and his father Stan wired and paneled the inside of the original cabin, and continually made additions and improvements. We celebrated his eighteenth birthday in the one-room cabin, with friends and neighbors wall to wall.

Stano learned a lot working with Goodie. He designed and built the ham shack, the two-car garage, and the cram shack. His dad and the kids helped, but they are Stano’s buildings.

Stano insisted on building better than code. One inspector was so impressed he signed it off on the second inspection saying it was way above code and he could see it was being built properly. No short cuts. Although everything fell out of the cupboards in the 1992 Landers magnitude 7.3 earthquake, there was no structural damage done to the house.

During one of the summers Stano stayed with the Goodridges, he and Goodie installed tile in the big room. We arrived and were surprised with the beautiful new flooring on the old concrete, an anniversary present to us. Stupendous.

Perl and Dad gave us the dining room furniture… big Spanish table, sideboard and dish cabinet. Many a dinner was served with a full table, often the DuMonds were the guests. For a couple of years we put out The Desert Whispers, a small paper of mostly local news and some items that concerned the valley. It was put together on the dining room table.

Stano met his first wife Karan at the desert. When their two sons, Jonnathan and David, got their running legs, we often took them with us to the desert.

At times during the summer when Stano was not teaching but his father and his wife were working, Stano and the kids and I went to the desert, and Stano worked on the buildings. The kids spent a lot of time playing with small cars in the sand. They also became expert roofers. These were very good times.

There was one baddie. Stan was trying to fix a second-hand air conditioner when he tangled with the fan and made a deep gash across the back of his hand. Stano drove him thirty miles to the hospital in Yucca Valley while I phoned to let them know he was coming.

The hand was repaired and suffered no permanent damage. Another time David fell off one of our three-wheelers. His ankle looked bad. I called 911 and in no time the house was filled with seven emergency medics. He went by ambulance to the Yucca Valley Hospital while I drove the car. It was a bad sprain and he was bandaged and released. I drove home… pitch black… missed our road, and went almost to Old Woman Springs before discovering my mistake and turned around to come back. Who was rattled?

Sometimes I stayed alone for several days in the cabin. We had CB radios to call each other. One night a car drove across our property and the lights disappeared in the wash, with no more sound. I called Dick DuMond. He brought friends and they looked around and found no one. Everyone retired for the night.

In the morning there was a car in the wash on our property and a guy walking around. I called Dick, and he arrived, well armed. We went over to the car. The guy said he was drunk and lost his way so he just slept it off where he was. We heard later he told his friends he was scared to death when a big guy with a gun and a wild woman waylaid him in the wash.

Another night when I was alone the Taylor house up on the hill was burglarized and their truck was stolen. I heard noises and called the sheriffs but they did not respond. I discovered things were open the next morning, and reported it, but I still feel guilty that I was not more aware of what was happening.

We joined the Johnson Valley Improvement Association and became well acquainted, and participated in the action. There was a lot going on, a few mild controversies. The DeVictoria shooting was worst, and a few people left the valley after that.

But for the most part it was fun and games, with some work thrown in. We hauled the organ to DeVictoria’s Chisel Inn one Saturday night and Stano provided music all evening. We made some friendships that have endured.

The cabin is a house now, filled with a great many superb memories, like a well-built house should be.

§ § §

This three-minute drone video takes you up into the JV sky, and was shot by George Cayer, our good friend and neighbor.

§ § §

Epilogue—This parcel was our family homestead for sixty-five years. Now, at the age of 78, it has become a maintenance headache for me. Since moving to Tehachapi during 2014 to another ten-acre parcel that was inherited by my wife, our time and energy are required in Kern County. The JV property means a lot to us, but its maintenance requirements are beyond my abilities. Thank goodness a JV realtor and I are friends, and he found the perfect person to become its new owner, who is delighted with it. —Stan Coutant

During 2022 the Los Angeles Times published two stories on “California’s abandoned homesteads,” first on June 7, with a follow-up on August 12. Story № 1 includes thoughts from Melody Gutierrez, member of a family who owned and lived in one of the now-abandoned cabins. Story № 2 is a photo display of several similar structures in the same sector.

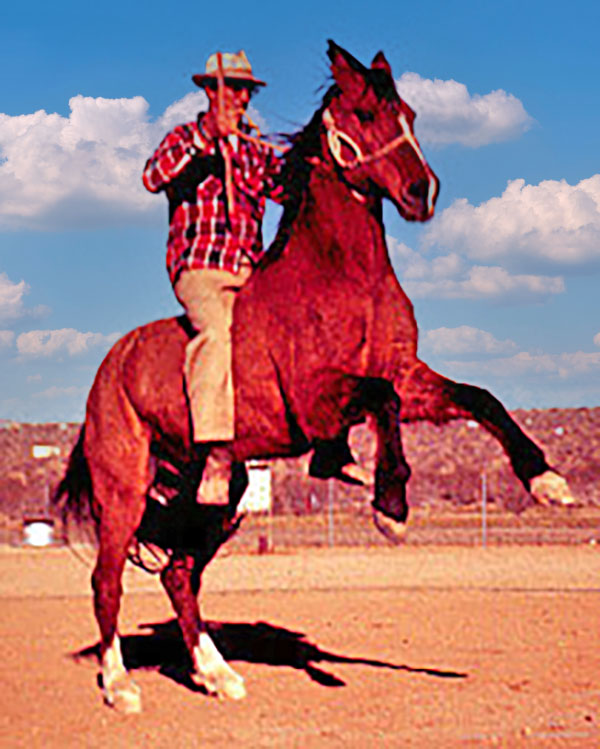

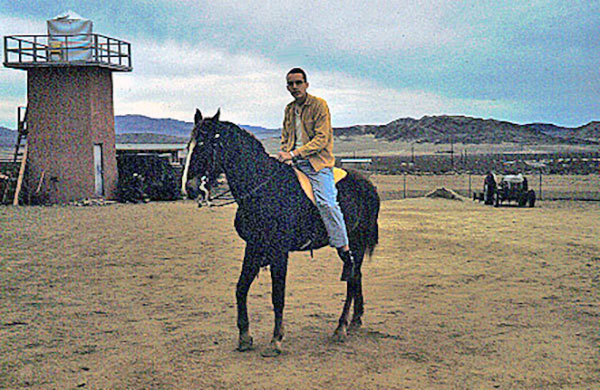

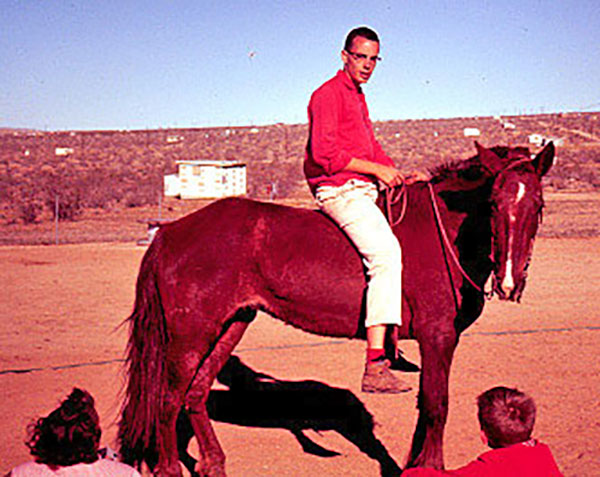

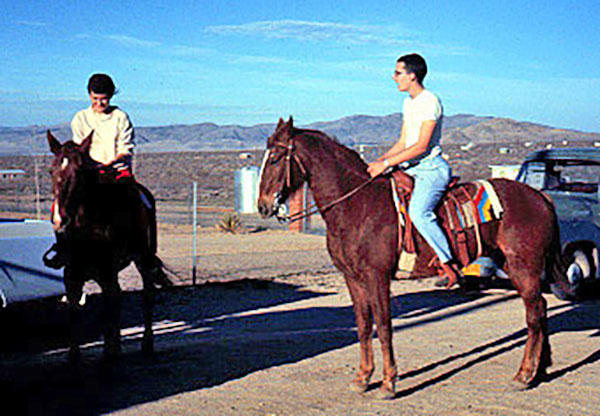

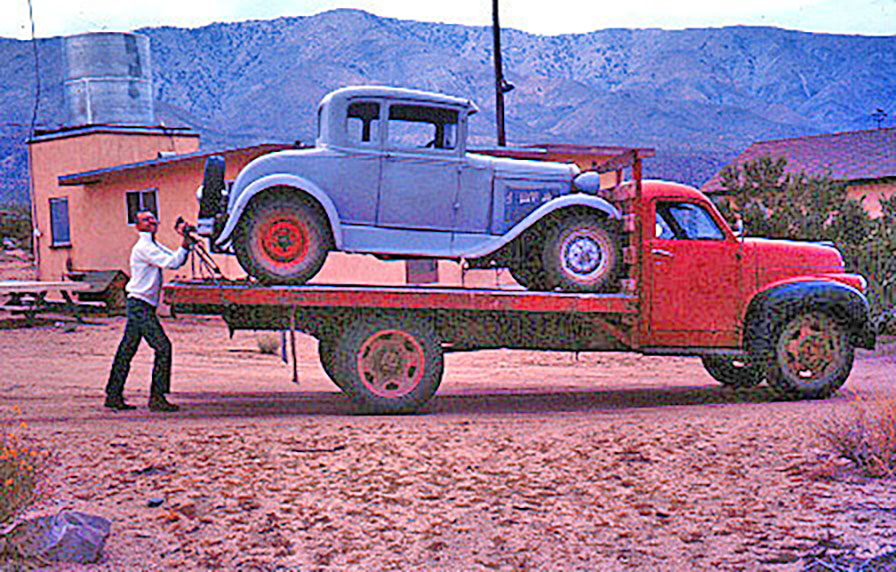

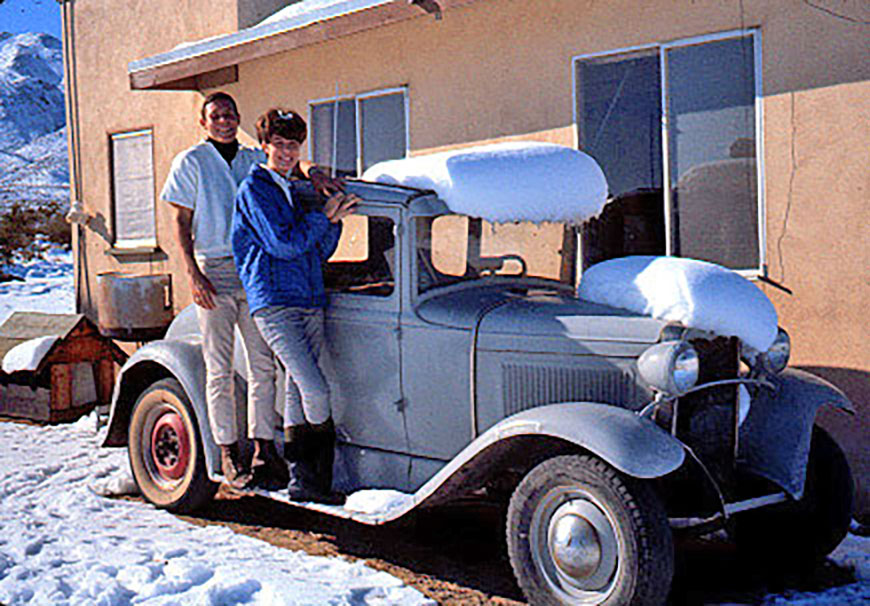

February, 2024 is when additional Johnson Valley horse, tractor, car, and truck transparencies were discovered. Some are low resolution. Here they are for your viewing pleasure.

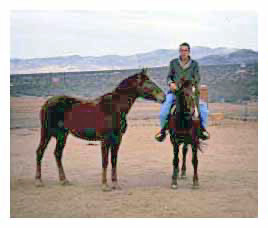

Goodie on Buck, a gelding.

Holly, a mare.

Stan on Holly.

Stan on Robin, a mare.

Stan on Robin.

Zilla on Robin, Stan on Holly.

Goodie gives Stan a raise.

One of two ’dozers Goodie and Stan found at an inactive mine.

The second ’dozer, this one a Caterpillar.

An International-Harvester Stan was hired to operate, equipped

with a Drott 4-in-1 bucket: loader, ’dozer, clamshell, scraper.

Bill Lindquist pretending to lift Stan’s 1931 Model A Ford

German Shepherd Cindy in the ’31 Ford before it was repainted.

Charlie Keyes delivers concrete for the Coutant garage floor.

Friends Doug and Frances helped Stan spread the mud.

Jim and his sweetheart pose with the ’31 Ford after a snowfall.

DuMonds and Coutants work together to raise an antenna pole.

Stan’s 1931 five-window coupe and 1930 Cabriolet Coupé.

Stan’s friends from Pasadena City College visit Johnson Valley.